Implementing QUIC from Scratch with Rust: TLS 1.3 Handshake and QUIC-TLS Key Update

Quick Overview of TLS 1.3

Related Security Algorithms

Even though I use TLS a lot at work and sometimes have to dig through OpenSSL code just to stay alive, I am nowhere close to a security expert. So I want to share, based on my shallow view, what the core pieces of TLS are, why we need them, and which security algorithms show up. All the deep crypto math is handled by the ring crate.

If I must describe TLS in one sentence, I would say TLS uses asymmetric crypto to agree on symmetric keys and then uses those symmetric keys to protect upper-layer data. That raises the usual questions: what is asymmetric crypto, what is symmetric crypto, why can’t we just use symmetric keys, and how does the safety really work. It sounds like textbook talk, but if we can explain the “why” in a few lines it is still worth it, because knowing the reason is the first step to knowing how.

Symmetric algorithms use one key for both encryption and decryption. They are mainly bit operations so they are cheap, but once someone learns the method they are easy to crack. Asymmetric crypto owns two keys: the public key encrypts and the private key decrypts. It is safer than symmetric crypto but the math is complex and slow. So TLS only uses asymmetric keys during the handshake to agree on symmetric keys for later traffic, which gives us both the safety of asymmetric crypto and the speed of symmetric crypto.

The common asymmetric algorithms are RSA and ECDH. The biggest impression I have is that ECDH gives forward secrecy. Forward secrecy means that even if the public-private pair leaks, past traffic stays safe. Why? Besides the key pair, ECDH also relies on a temporary secret that lives only in memory (math symmetry ensures it never goes over the network and we do not keep it), so we can keep forward secrecy. In TLS 1.2 you could negotiate RSA or ECDH, while TLS 1.3 forces ECDH for the handshake.

There are many symmetric ciphers: AES-GCM, AES-CBC+HMAC, and ChaCha20-Poly1305 to name a few. What stands out to me is that AEAD ciphers are now the default. In one sentence, AEAD gives both encryption and integrity in one go, while AES-CBC+HMAC splits encryption and auth so it is not AEAD. Compared with TLS 1.2, TLS 1.3 forces AEAD ciphers and drops slow or unsafe ones such as 3DES and AES-CBC. I was curious about ChaCha20-Poly1305 versus AES-GCM. I always thought AES-GCM was the first pick, so ChaCha20-Poly1305 must shine somewhere. A quick search shows AES-GCM wins when you have hardware acceleration. Without hardware help (phones or low-power devices), ChaCha20-Poly1305 performs better.

TLS uses key-derivation algorithms to stretch the shared secret (before I hand-wrote this project I did not even know such a thing 😂). It makes sense: asymmetric exchange usually gives one secret, yet TLS wants to use different keys in each phase. We cannot redo the handshake every time we rotate keys, so key derivation is needed. Besides flexibility it also boosts safety because we iterate the base key several times. TLS 1.3 uses HKDF, while TLS 1.2 used PRF. Both are built on HMAC, but folks say HKDF is safer and more flexible, an upgrade over PRF. Please don’t ask me to detail the difference, I have no energy for that right now.

Last but not least we have digital certificates to prove the public key is trustworthy. The belief in asymmetric exchange relies on a trusted public key. When I wrote the code I skipped certificate checks because life is short and figuring out HKDF for TLS 1.3 already took all my strength.

TLS 1.3 vs TLS 1.2 Handshake Details

Let’s compare the handshake tweaks after TLS moved forward, because I need a simple TLS 1.3 client and the handshake matters the most. First, the biggest difference is that TLS 1.3 only needs one RTT, while TLS 1.2 needs two. I think this is not because TLS 1.3 uses ECDH, but because TLS 1.3 adopts weak negotiation and TLS 1.2 uses strong negotiation. My take: TLS 1.2 lists all its supported asymmetric algorithms and cipher suites when the client starts the handshake, waits for the server to pick and confirm, and then runs that key exchange. TLS 1.3 also lists what it supports but already picks a few choices and starts the exchange instead of waiting for the server to confirm.

This style is simpler. There is no need to wait for the server reply before doing work. Extensions such as Key_Share are built to let TLS 1.3 pre-negotiate. TLS 1.3 also removes unsafe ciphers, which further helps weak negotiation: fewer options mean a higher chance to agree, and we still have Hello Retry Request as a fallback.

Next, the handshake flow is cleaner. TLS 1.2 had the ChangeCipherSpec message to tell the peer that the next handshake data would be encrypted. TLS 1.3 drops it. In TLS 1.3 (ignoring 0-RTT), client_hello and server_hello are in plain text for the asymmetric exchange. After that both sides can encrypt, so later handshake messages such as encrypted_extensions are protected. When the finished message passes verification, the TLS 1.3 handshake ends. So ChangeCipherSpec has no role to play.

Finally, TLS 1.3 strictly defines when to throw away keys. After each phase you must drop the related keys. That is great for safety, especially forward secrecy. QUIC-TLS likewise defines when to drop Initial and Handshake keys.

Key Update

Purpose and Effect

This Key Update mechanism was introduced in TLS 1.3 so that either side can swap out the symmetric key from time to time to raise safety. There is also an extreme case: AEAD ciphers have data limits, and using the same key too much weakens the safety of AEAD. Key Update is simple: use HKDF again on top of the agreed key following the rules in the spec.

Differences Between TLS 1.3 and QUIC

I could stop the Key Update intro here, but QUIC improves it a lot. I spent extra time to understand the design so I want to summarize what I learned. Above I only said we update the symmetric key via HKDF, but I did not mention the key detail, namely how Key Update is triggered.

First, let’s check TLS 1.3. After the handshake (both sides received each finished), Key Update can happen at any time. One side can send a key_update message to tell the peer to rotate keys. The sender then encrypts later data with the new key. The receiver updates its key after reading key_update, and sends its own key_update back so that its later data also uses the new key. Because the channel is full duplex, each side must send key_update before switching its sending key, which is the reasonable thing to do. Even if both sides want to rotate at the same time, they just exchange key_update messages and the protocol keeps working. If someone implements it poorly, the worst result is that we rotate twice.

But QUIC-TLS cannot reuse the TLS 1.3 design. QUIC-TLS is tightly fused into QUIC and does not sit on a reliable byte stream, so sending a key_update message in-band is not a good idea. QUIC-TLS takes a neat approach: in QUIC Short Header packets (application packets) there is a key_phase bit that shows whether the key changed. Key Update only happens after the handshake, so only Short packets need this bit. For safety the key_phase bit is protected by QUIC Header Protection. You might wonder if the Header Protection key also changes. The answer is no. Key Update does not touch the Header Protection key. I think this ensures the receiver can always handle key_phase.

Here comes the key question: can key_phase handle out-of-order QUIC packets? Imagine the sender triggers Key Update and uses key_phase to tell the receiver, but packets arrive out of order. The receiver sees the bit flip, updates its key, yet an old packet encrypted with the previous key shows up late. Do we just drop it and rely on retransmits? The QUIC RFC suggests delaying the removal of the old key (for example, wait for three PTO) so we can still decrypt out-of-order packets and reduce the impact on throughput.

I also wondered if the key_phase bit can handle every case. Again, think about old packets arriving late. The stack notices that the old packet has a different key_phase. Should it rotate again? The answer is simple: if the packet cannot be decrypted with the current key, we should not rotate. Likewise, if we already dropped the old key and the packet fails to decrypt, we clearly should not rotate. In short, only packets that can be decrypted with the current key and have a flipped key_phase are allowed to trigger the update. As long as we follow this rule, even if both sides start Key Update at the same time we can handle it. That is how QUIC Key Update works.

SSLKEYLOG

When we debug TLS traffic we usually export an SSLKEYLOG file from the SSL stack and let Wireshark decrypt the packets. It works great. There are many eBPF tools today that grab clear text straight inside SSL libraries or even the app itself, but that is not our topic today.

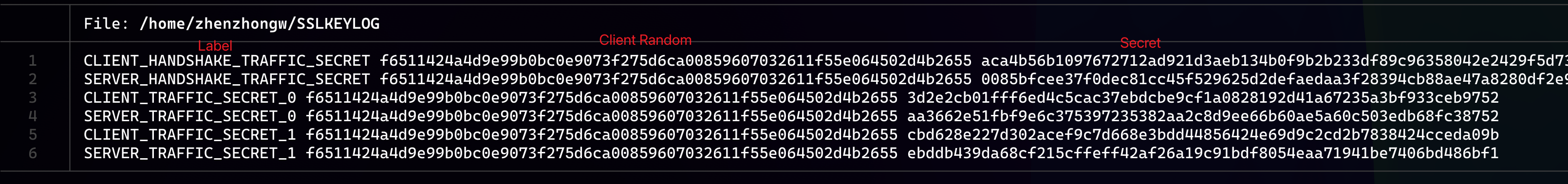

So to debug feather-quic better, I added support for generating SSLKEYLOG files. Honestly, when I use it I rarely pay attention to the layout. I only know that symmetric keys live there. To implement SSLKEYLOG I first looked up its RFC.

The RFC is clear: each line stands for one key and has three fields. The first is the label that shows the key type, such as handshake or application. Key Update rotates keys, so the handshake and application labels have numbers on them so we can bump the number after each update. It just dawned on me that when I saw tons of keys in SSLKEYLOG before, it was because of Key Update.

The second field is client_random, which is the Random field from the client_hello. It identifies a TLS connection. The third field is the symmetric key shown in hex. So we can easily generate SSLKEYLOG files while TLS 1.3 is handshaking and use them for later debugging.

Implementation Details

First of all I truly thank TLS 1.3 for trimming so much compared with TLS 1.2. It makes my life much easier. I also thank ring for covering the crypto I really did not want to touch, such as using ring’s X25519 for the ECDH exchange and the other strange primitives like AES-GCM and HKDF.

But I stepped hard on a HKDF landmine, which hurt a lot and took quite some time. Looking back, I was unfamiliar with HKDF so I called the ring API incorrectly. I thought it would be easy: just provide the inputs HKDF needs. Yet the Prk::expand API is wild. The info parameter is a byte slice with an awkward layout. If this were C code I would not mind, but this is Rust and ring could have given a tiny wrapper instead of making me fill it myself 😭. I spent time reading the rustls crate to learn how to call it. The docs are also very brief and never explain the info parameter; they just link to the HKDF RFC. It seems they expect only professionals to use it, not a security amateur like me who is bored enough to call ring directly.

Another rant: the TLS 1.3 RFC describes the HKDF steps in a very concise way, which is not friendly to someone like me who just wants a fast prototype of TLS 1.3 HKDF. To be clear, I am not saying the RFC is bad. I think it is great, but I need more time to understand it (yes, that is on me). I had to print every stage of the key schedule and compare it with OpenSSL output before my code worked. Thankfully there is a full TLS 1.3 key schedule sample online, which helped me a lot. Fun fact: I googled the fixed hex of the initial TLS 1.3 secrets and that is how I found it 😉.

Finally, to finish the handshake smoothly I generate the client finished message strictly by the RFC so that the server can verify it. But I do not validate the certificate nor the finished from the server, just like I said earlier—this is only a learning tool. Maybe one day I will repent and use a solid SSL library to power feather-quic.

Epilogue

By now the QUIC handshake part is mostly done. On the QUIC-TLS side, the only missing piece is 0-RTT, which is both the hardest and the most fun. Before I work on 0-RTT I want to finish the QUIC reliability features, because without retransmits and acks QUIC cannot really run. After I get the core QUIC features in place I will come back for the fun 0-RTT work. I also need to think hard about how to test all the corner cases, since some of them are tricky to cover. I will try to fill those tests as I add new features.

Here are the PR and the branch for this article. It took longer than planned because Overwatch came back to China and I have to play a bit every day. I also started to try Marvel Rivals (learning a new game is harder than learning a new tech, seriously), my Diablo IV season six pass is still unfinished, and I even stayed up late this weekend to binge-watch season 3 and 4 of Slow Horses. I am exhausted 😭.