Implementing QUIC from Scratch with Rust: Trying to Dive into the QUIC Handshake 😂

Why Is the QUIC Handshake So Complex

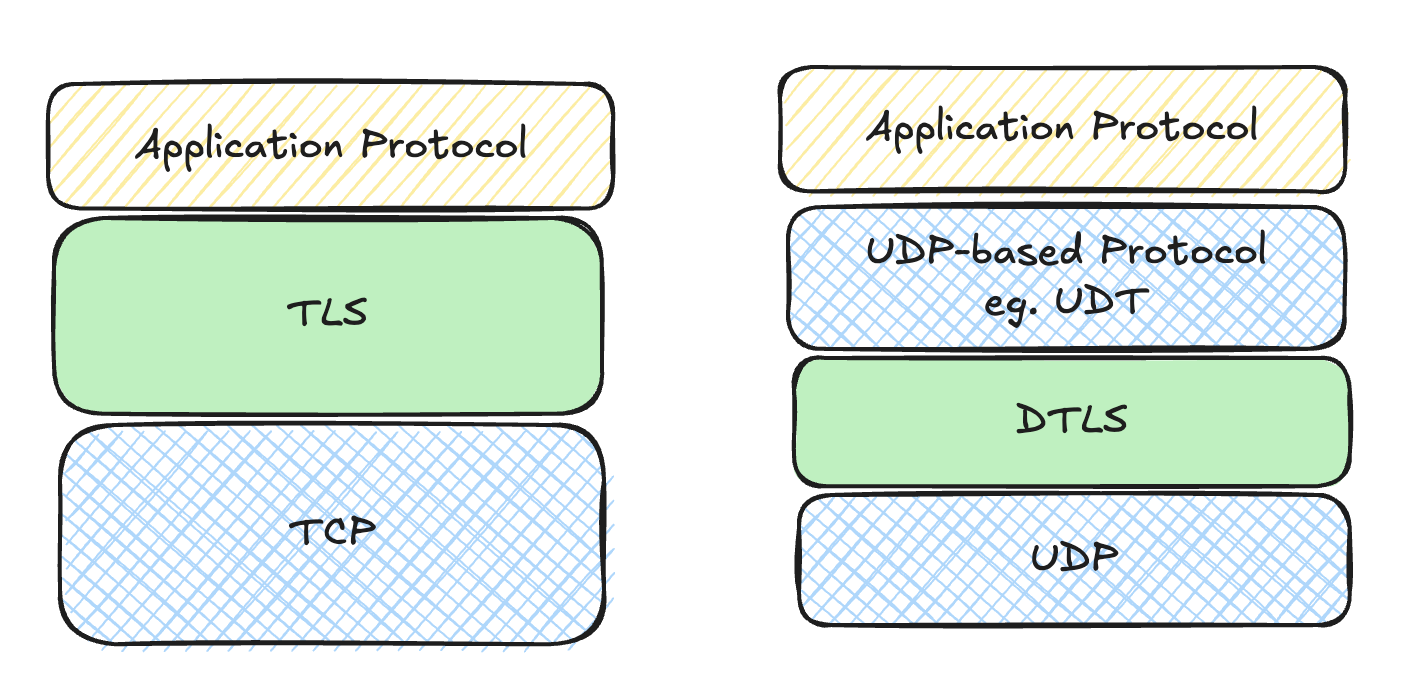

Compared with TCP or other UDP-based protocols, the QUIC handshake is much more complicated. The first reason that comes to mind is that QUIC builds TLS 1.3 directly into the transport layer to keep application traffic safe. QUIC did not follow the old pattern of stacking transport and crypto layers (for example TCP + TLS or DTLS + UDP protocols like UDT). It fused TLS 1.3 into the protocol itself, so we now have QUIC-TLS.

Why Do We Need an Encryption Layer

Before talking about the handshake design, I want to restate why we need an encryption layer. The main reason is still security: if we follow the TLS rules, communication between two peers can stay safe from man-in-the-middle attacks.

Another benefit is that it prevents protocol ossification. TCP and TLS are decoupled, so many middleboxes on the path (for monitoring, security, QoS, etc.) will tweak TCP packets. Even if we ship a new TCP option that follows the spec, those old boxes may break the traffic, and we cannot upgrade them quickly. Once they are placed in a network, cost and reliability make upgrades rare.

QUIC traffic is encrypted end-to-end, so middleboxes cannot look inside and do “smart” things. That helps QUIC stay flexible and evolve even if middleboxes stay frozen in time.

The Difference Between DTLS and TLS

Most UDP-based transports rely on DTLS, while TCP-based transports use TLS. DTLS sits between UDP and the protocol above it, and TLS sits on top of TCP. DTLS was designed from TLS, so it aims to provide the same safety level. The biggest difference is that DTLS has to adjust TLS so that it can work on top of an unreliable datagram stream.

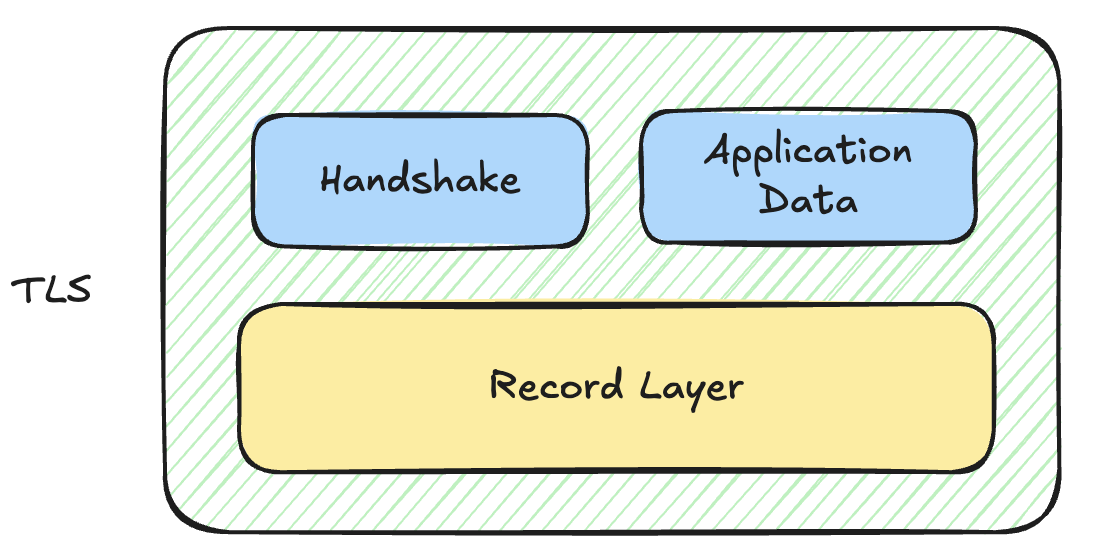

The TLS handshake mainly negotiates an asymmetric key and then derives symmetric keys that protect later traffic. Only the early handshake messages are sent in plain text; once the symmetric key is ready, those handshake messages are encrypted too.

So DTLS first has to make sure those symmetric-key-protected messages still work on an unreliable transport. Regular TLS uses a MAC that depends on the TLS Record layer sequence number. TLS Record messages run on a reliable stream, so the receiver can compute that sequence number by itself. DTLS cannot do that because UDP does not provide reliability, so DTLS Record messages carry explicit sequence numbers.

The sequence number also feeds the sliding window and protects against replay attacks. UDP has no three-way handshake, so even an off-path attacker can forge traffic. DTLS must also ensure that one UDP datagram carries a complete TLS Record, otherwise the sequence number means nothing. Reliability for Application Data still has to come from the protocol above DTLS, such as UDT or KCP.

DTLS also has to implement a simple ARQ to keep the handshake in order. Data reliability can be handled above DTLS, but the handshake is DTLS’s own job, so it must retransmit handshake messages, confirm delivery, and face all the usual ARQ problems. I plan to describe those issues again when I work on QUIC Reliability.

TLS itself assumes a reliable stream, so DTLS needs more changes. For instance, DTLS 1.2 uses TLS 1.2, where ChangeCipherSpec is the signal that data will be encrypted. On an unreliable stream we can see reordering and loss, so the receiver needs extra help. DTLS Record adds the epoch and Sequence Number fields. epoch tells the peer whether this record is already protected, so it replaces the ChangeCipherSpec signal.

TLS handshake messages, especially ones that carry certificates, can easily exceed the UDP MTU. DTLS has to make sure each UDP packet carries a complete TLS message, so DTLS must split and reunite handshake messages by itself to avoid IP fragmentation. Protocols built above DTLS will probe and respect MTU once the handshake is done, but the handshake itself is DTLS’s responsibility.

QUIC could have reused DTLS, but it picked a cooler design. I am describing these DTLS details because QUIC faces similar problems when it designs its own handshake.

The Role of TCP’s Three-Way Handshake

Let us revisit the famous TCP three-way handshake. Many people are tired of this question, but looking at it from the point of view of a transport designer helps. When a transport needs reliable and ordered delivery, it needs sequence numbers. DTLS numbers each message, while TCP numbers the bytes. The first task is therefore to agree on where the sequence number should start. If TCP decided to start at zero every time, two things would go wrong:

- Attackers could guess the sequence number of a connection that is identified by a four-tuple, then send fake packets to disrupt it (tools like tcpkill rely on forged RST packets).

- A new TCP connection might receive old packets from a previous connection that used the same four-tuple, especially on a busy server or when some kernel options are turned off.

I once worked on a project that pulled KCP into NGINX. KCP always starts from zero because it has no built-in handshake. During a late-night call a customer said reconnecting broke the service. They kept the old KCP context and reused it, so the new requests did not start at zero. Without a handshake, they had to manage that part themselves.

Back to TCP: the handshake also confirms both ends are real. If an attacker spoofs the source address in a TCP SYN and there is no handshake, the victim will send data to an innocent host and waste CPU/memory. With three steps, both sides prove they control their addresses before sending real data.

The handshake also negotiates transport parameters such as window size, MSS, and options like SACK. These parameters are key to performance.

Next we can look at what TCP taught us. TCP suffers from weak security. On-path attackers can still mess with TCP packets, which is why TLS appeared. TLS uses DH-style key agreement (e.g., ECDH) and certificates to block those attacks, but TLS only protects the payload on top of TCP. Attacks on the TCP link itself still work. On top of that, a client needs one RTT for TCP and one RTT for TLS 1.3 before it can send real data. Two RTTs feel slow.

Can We Merge TCP and TLS Handshakes

People have proposed merging the two handshakes, but TCP has hardened over time and kernel upgrades are hard, not to mention backward compatibility. Most proposals stayed as drafts.

It is still fun to think about it. If the traffic were encrypted (even though only the later part of the TLS handshake is protected), sequence numbers could finally start from zero because nobody else would know them. Packets from different connections would also be safe because the encryption uses a MAC to confirm authenticity. But just stacking the TLS handshake on top of the TCP handshake does not unlock those benefits.

If we insist on merging them and still want a three-step handshake, new problems appear. TCP’s three steps verify that both sides are real, but TLS would have to trust the peer before the third step, which is unsafe. Think about SYN-flood attacks: the attacker wants the server to burn CPU. TLS consumes even more CPU than TCP, so a combined handshake would be risky.

So a simple merge does not fix much and brings more trouble. QUIC was designed in the last decade, so it could absorb these lessons and start fresh. Let us see how QUIC handles the handshake.

How QUIC Builds Its Handshake

The problem statement can be said in one sentence: QUIC must provide a reliable byte stream for QUIC-TLS, and QUIC-TLS must provide security for QUIC. QUIC’s answer is to fully merge with TLS 1.3 so that each part helps the other.

How QUIC Provides a Reliable Byte Stream for TLS 1.3

After the handshake, TLS uses the negotiated symmetric keys to encrypt and decrypt QUIC payloads. You can think of QUIC as the TLS Record layer. QUIC’s ARQ implementation keeps the TLS handshake and later data running on a reliable byte stream.

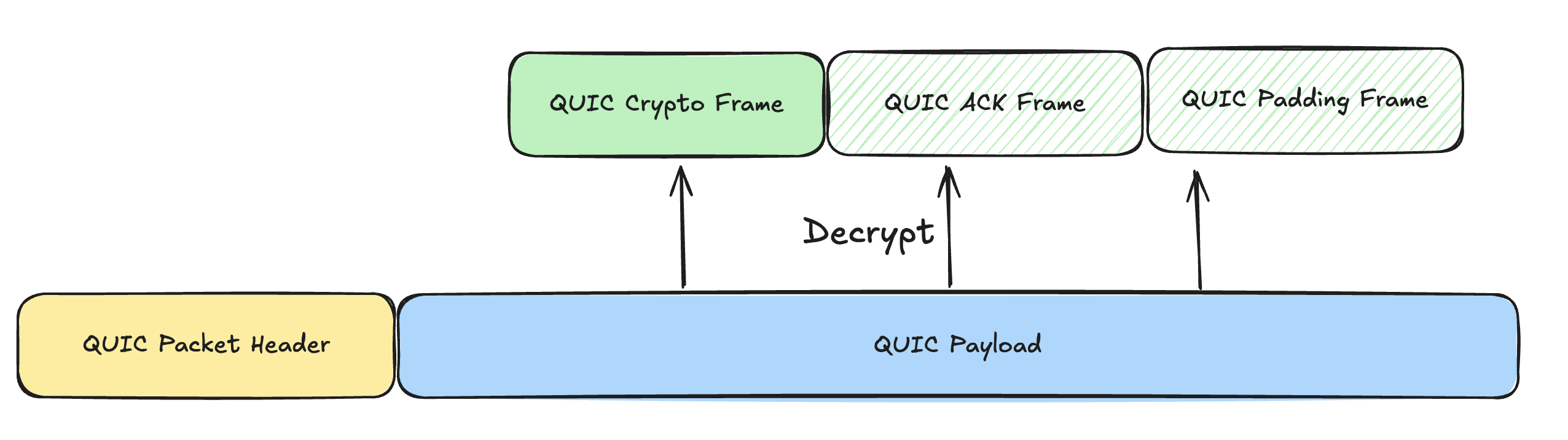

During the handshake, QUIC carries TLS handshake data inside QUIC Crypto Frames. Each frame has offset and length so that TLS 1.3 sees the same ordered stream it expects from TCP.

QUIC also provides a frame abstraction. Many control signals that live inside the TCP header (SYN, FIN, ACK, sequence numbers) are split into different frames in QUIC, so control and data are decoupled. QUIC packet numbers never try to describe the order of the carried data. Each frame that needs ordering—for example a Crypto frame—tracks its own offsets. This helps multiplexed streams, RTT calculation, reliability logic, and much more (I will cover those in later posts).

As a transport, QUIC still has to negotiate transport parameters to improve performance. Instead of storing them in a packet header, QUIC sends them through TLS as Transport Parameters. The TLS handshake is the only way those parameters travel, which again shows the tight fusion between QUIC and TLS.

How QUIC Uses TLS 1.3 to Encrypt

TLS messages can be roughly grouped into TLS unencrypted Handshake, TLS encrypted Handshake, and Application Data (ignoring 0-RTT and Key Update for now). QUIC follows the same idea but separates packets into three spaces: initial, handshake, and application. Each space has its own packet number sequence and its own ARQ state.

QUIC encrypts each packet payload with the symmetric keys that TLS 1.3 negotiates. The three spaces use different keys. The initial space is almost in plain text because the key is derived from a public salt in the RFC—think of it as “keep honest people honest.” The handshake and application keys come from TLS’s handshake and application secrets and are derived again with HKDF as required by QUIC-TLS.

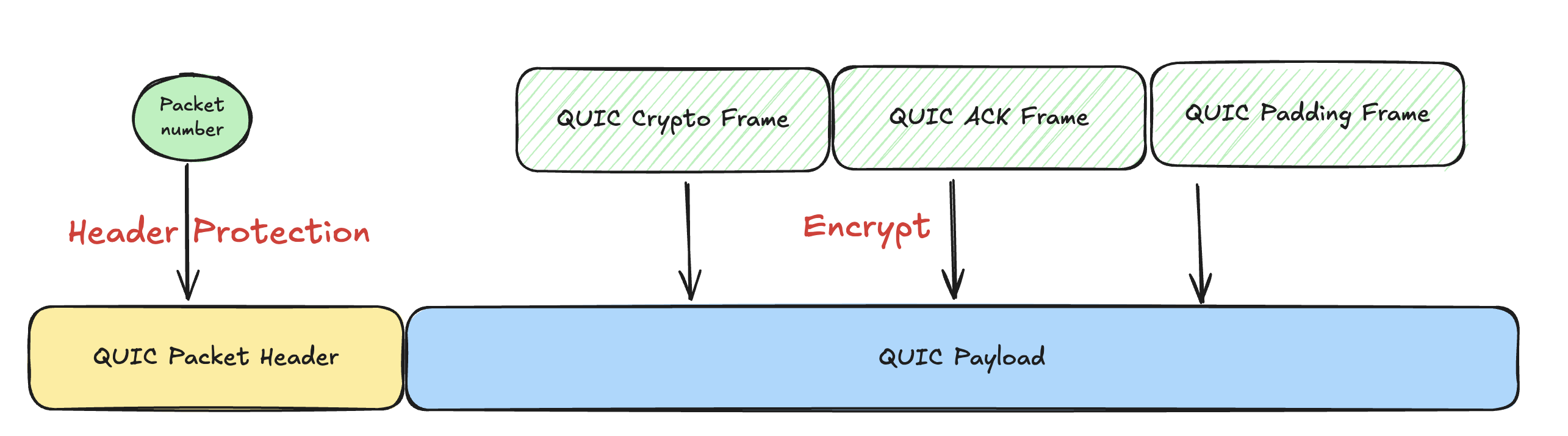

Protecting the payload is not enough, so QUIC also adds Header Protection (HP) to hide the packet number and some flag bits. HP uses AES-ECB, which is lighter than the AEAD mode used for payloads. It has some security limits (I could not find AES-ECB inside ring because it is considered unsafe), but it is fast and good enough for headers.

When building a packet, QUIC encrypts the payload first and then applies header protection. When parsing, it removes HP before decrypting the payload. This way the QUIC layer can know the packet type and packet number early, which helps with duplicate detection and other transport logic.

QUIC Retry

So far the handshake can provide transport semantics and TLS security, but one more problem pops up. A TCP three-way handshake can verify that the peer is real, but the QUIC-TLS handshake merges TLS messages into those three steps, so when we run the TLS 1.3 handshake the server still does not know if the client is real. A TLS 1.3 handshake costs a lot of server resources. QUIC does limit the server to three times the client’s handshake bytes, yet attackers can still try amplification attacks.

AEAD’s MAC check cannot help during the handshake because the peers have not agreed on keys yet. QUIC therefore adds a Retry step to verify both ends. It is similar to TCP’s request/response check, but instead of relying on sequence numbers, QUIC uses tokens and tags. The tag validation uses AEAD-style authenticity checks so a client can confirm a Retry packet is from the real server.

When we shipped our own UDP-based transport years ago, we made the same mistake and left an amplification hole. A teammate spotted it and fixed it quickly. DTLS also has HelloRetryRequest, which helps re-negotiate crypto parameters and confirm the peer, so the idea is quite similar.

Coding Notes and Ending

Now to the code. I did not use rustls or OpenSSL for QUIC-TLS. Instead I used ring and an AES crate to build the needed crypto pieces. As I wrote before, QUIC handshakes are fun, and using a ready-made SSL stack would remove too much joy. The cost is that I cannot reuse the stability and security guarantees of a real SSL library, but that matches the spirit of this side project. Reading the NGINX QUIC implementation in the past gave me the confidence to try this route because NGINX can work even when OpenSSL does not support QUIC.

My first task was to derive the initial keys according to the RFC. That part was painful because I am not familiar with every crypto detail. During debugging the NGINX server told me my keys were wrong, so I read OpenSSL and rustls code side-by-side until I found the bug. Once the initial key derivation worked, the same function could derive the handshake and application keys by using the TLS-provided secrets instead of the RFC salt.

When I implemented QUIC Retry, I still had no TLS 1.3 handshake code, so for debugging I forged the TLS payload inside Crypto frames. Luckily NGINX did not check the early Crypto contents strictly (or OpenSSL’s do_ssl_handshake had not had a chance to complain), so I could verify my Retry logic easily.

There are many other QUIC details—packet length encoding, packet number compression, and so on—that I have to study carefully in the RFC even if I did not mention them here. I also added many CLI arguments to the client so that I can test different scenes, such as customizing the first handshake packet length or setting Source Connection ID and Original Destination Connection ID.

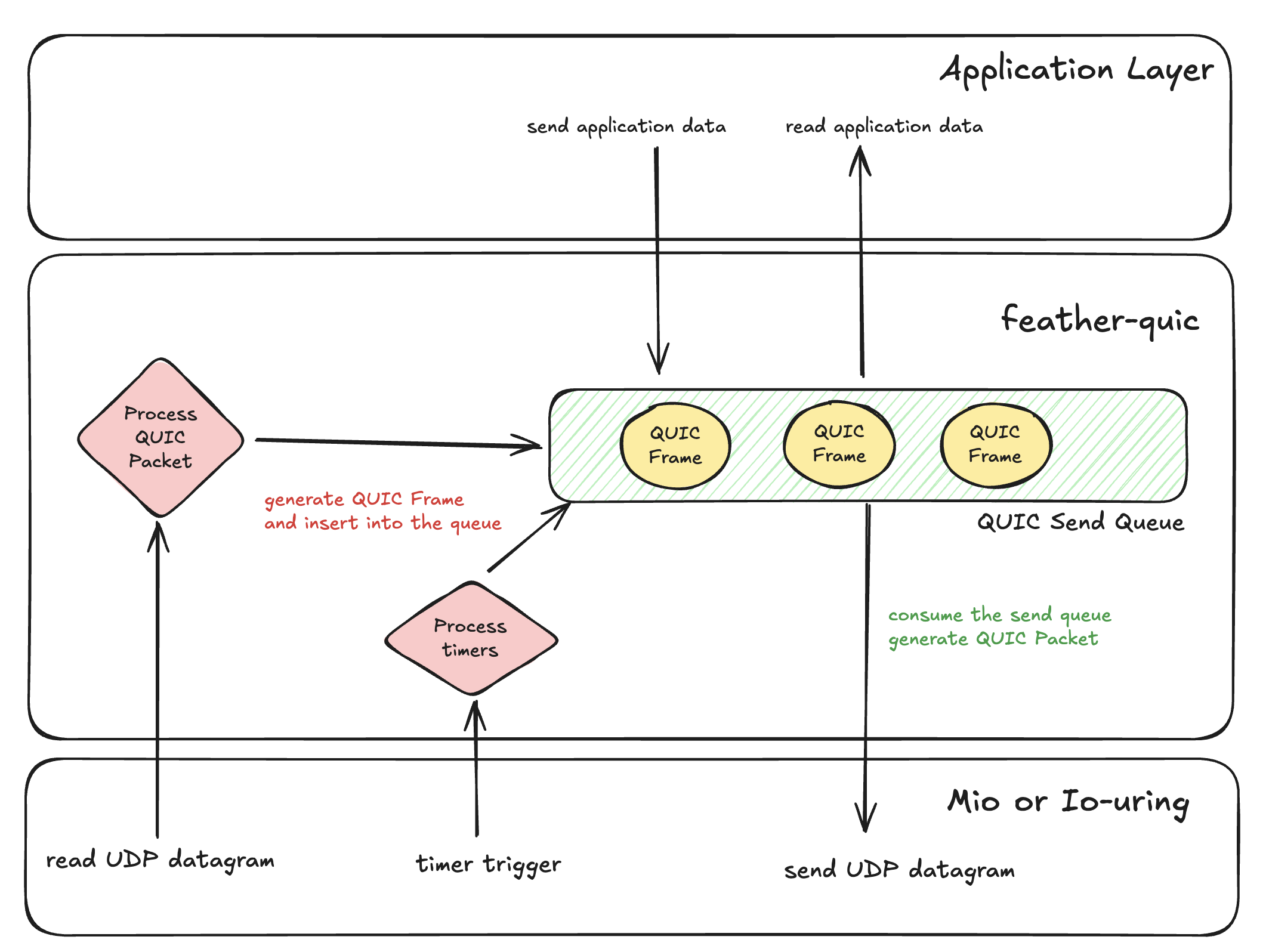

Although this post only covers the handshake, I still had to design the basic send queue for feather-quic. I had to choose whether the queue tracks QUIC packets or QUIC frames. Because QUIC will need retransmissions for ARQ and QUIC-TLS allows Key Update, retransmitting a packet may require re-encrypting it. Therefore the send queue must store frames, not packets. Frames can be packed by priority into any packet and each frame can track whether the peer acknowledged it, which makes future features possible.

In short, the QUIC handshake is complex but worth learning. This post only talks about the QUIC-TLS integration and not the TLS 1.3 handshake itself. The related code sits in PR #1 and the handshake branch. The next post will cover the TLS 1.3 handshake implementation.